Women of History: Sarah Pike Conger

Sarah Pike Conger, Edwin H. Conger, and a niece at the United States Legation Building, Beijing, China, c. 1900, P00477.

Listen to this article

I love my precious religion as I never before knew how to love it. It does prove to be a power of strength in a time of need….1

In letters written during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, Sarah Pike Conger frequently mentioned her faith and how it carried her through those difficult months. The wife of the American minister in Beijing, China, during the siege of the city’s foreign quarter, Sarah was a source of comfort for others.

She was born Sarah Jane Pike in Ohio on July 24, 1843. Her parents encouraged her to pursue an education, which blossomed into a lifelong love of learning. Sarah attended Lombard College In Galesberg, Illinois. There she met her future husband, Edwin Conger. Their relationship was a partnership of equals, which Edwin described in a letter to their daughter: “If you will have implicit and unfailing mutual confidence, make it a point to always consider the other more than self.”2

After a domestic political career, Edwin Conger was appointed foreign minister to Brazil in September 1890. The Congers moved to Petrópolis, providing Sarah with her first taste of life outside the United States.3 Her desire to understand the people around her forced her to reevaluate her “attitude of superiority.”4 In an 1898 letter to Mary Baker Eddy, Sarah wrote: “I have ceased comparing and contrasting this people with my own dear countrymen.… There is one brotherhood.”5 Sarah had joined The Mother Church in January 1894 and she went on to become a teacher of Christian Science. While her letters to Eddy do not reveal specific details about how she became interested in Christian Science, she frequently expressed her gratitude for it. The two women maintained a correspondence for the rest of Eddy’s life.

In January 1898 Edwin was appointed minister to China, and that summer the Congers arrived in the Legation Quarter of Beijing (then called Peking). Sarah, a supporter of women’s rights, was particularly interested in the experiences of Chinese women.6 But on her arrival she found she rarely interacted with women.7 Her wish was partially granted on December 18, 1898, when the wives of the foreign ministers were invited for an audience with the Empress Dowager Cixi.8 Sarah later recalled this meeting in a letter to her sister:

She was bright and happy and her face glowed with good will. There was no trace of cruelty to be seen. In simple expressions she welcomed us, and her actions were full of freedom and warmth. Her Majesty arose and wished us well. She extended both hands toward each lady, then, touching herself, said with much enthusiastic earnestness, “One family; all one family.”9

Sarah arrived in China at a tumultuous time. In 1898 a group known as the Boxers was gaining popularity and power in northwest China. They were anti-Christian and strongly opposed to foreign influence. In the spring of 1900, Chinese Christians and foreign missionaries were pouring into Beijing, seeking protection in the Legation Quarter.10 By mid-June the streets of Beijing were filled with Boxers.11 The delegations were trapped as the buildings around the Legation Quarter were destroyed. The ministers telegraphed their governments for support and troops were deployed—but it would be weeks before they reached Beijing.

On June 18, 1900, the Chinese government informed the ministers that they had 24 hours to leave the city. After that the government would withdraw its protection.12 Edwin and the other ministers concluded that it would be safer to remain in Beijing and wait for their soldiers.13

Sarah reported that Legation personnel, refugees, and missionaries worked together to fight the fires set by the Boxers.14 She joined them in making sandbags for the barricades, tearing clothing for bandages and retrieving supplies.15 One woman recalled that she became known as their “fairy godmother.”16 For Sarah, surviving the ordeal was an issue of faith:

I hourly give thanks. There is very much to give thanks for. My Christian Science is everything to me, and yet I wish I could do far more with it. There seems so much to be done in dispelling the darkness and letting the light shine. My heart often turns homeward to the dear Christian Science loved ones. I feel sure that you are giving us strong, protecting health thoughts.17

On August 14, 1900, international troops arrived in Beijing and relieved the legations, although some resistance continued in parts of China until the Boxer Protocol was signed in September of 1901.18

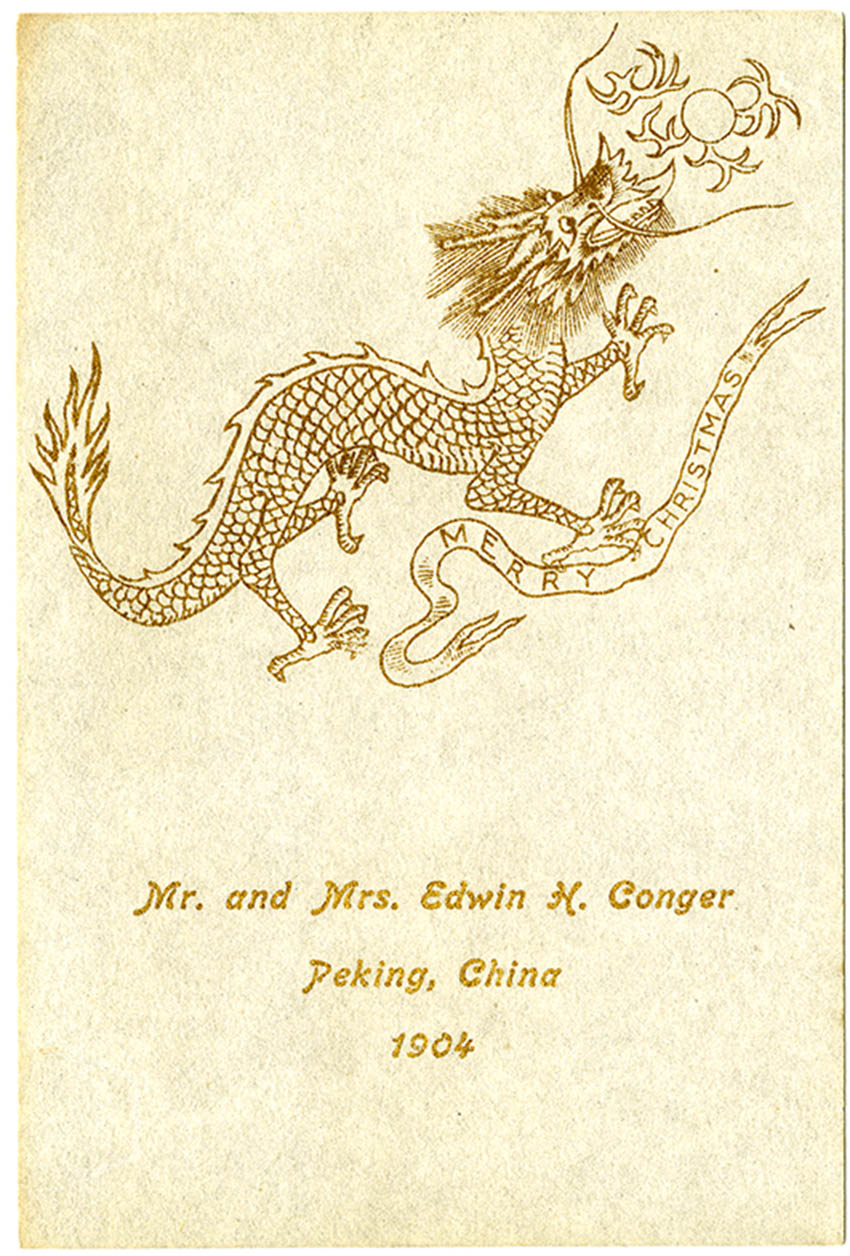

Christmas card from Edwin H. and Sarah Pike Conger, c. 1904. Library Collections, Subject File 38

The Congers remained in China. On February 1, 1902, Sarah again met the Dowager Empress, this time leading the women of the diplomatic corps. Sarah was the only woman at the reception who had been present throughout the siege. In her speech she expressed her hope for “more frank, more trustful, and more friendly relations with foreign peoples.”19

In 1905 the Congers returned to the United States and settled in Pasadena, California.20 Edwin died on May 18, 1907, his failing health impacted by the strain of the siege in Beijing.21 Sarah passed away in February 1932 at the Christian Science Pleasant View Home in Concord, New Hampshire.22 Throughout her years overseas, she sought to foster greater understanding between people. In her correspondence with Mary Baker Eddy after her return to the United States, she described how her faith influenced her life’s work:

Friendly relations was my mission to China, and I strove to establish and maintain these relations with the Chinese, with the diplomats, the missionaries, and all with whom I came in contact. God alone knows the rest…. What I succeeded in doing in China (through Christian Science,— not teaching nor talking it, but striving to live it) is wonderful.23

- “Siege of the Foreign Legations: Interesting Letter from Mrs. Conger, wife of United States Minister in Peking,” Christian Science Sentinel, October 11, 1900, 84.

- Grant Hayter-Menzies, The Empress and Mrs. Conger: The Uncommon Friendship of Two Women and Two Worlds (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2011), 7-8, 10.

- Ibid., 13.

- Sarah Pike Conger, Letters from China (Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co., 1909), 3.

- Sarah Pike Conger to Mary Baker Eddy, 7 January 1898, 026.10.003.

- Hayter-Menzies, 28, 32. In an undated address Sarah wrote, “Let us as women stand steadfast for Principle —Right— at every point, then with rounded lives offer a strong hand to help the world.” Sarah Pike Conger, Draft of “Woman’s Work!” address, n.d., 026.10.002.

- Hayter-Menzies, 83. Sarah Pike Conger, Letters from China, 2.

- Hayter-Menzies, 59, 61.

- Conger, Letters from China, 41-42.

- Trevor K. Plante, “U.S. Marines in the Boxer Rebellion,” Prologue Magazine, Vol. 31, No. 4, (Winter 1999): 1-2, accessed July 25, 2016, http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1999/winter/boxer-rebellion-1.html.

- Hayter-Menzies, 120.

- Plante, 1-2.

- “Siege of the Foreign Legations,” 84-86.

- Ibid., 87.

- Hayter-Menzies, 144.

- Ibid., 83.

- “Siege of the Foreign Legations,” 90. For an example of spiritual support given by Christian Scientists, see Peel, Robert, Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Authority (Boston: Christian Science Publishing Society, 1977), 421, n.32.

- Plante, 3.

- Legation Women see Dowager Empress,” Christian Science Sentinel, February 20, 1902, 392.

- Hayter-Menzies, 263.

- “Ex-Minister Conger Dead,” New York Times, May 19, 1907, 7.

- Hayter-Menzies, 276-277.

- “Christian Science and China,” Christian Science Sentinel, March 24, 1906, 467.