From the Collections: A remarkable story of persistence

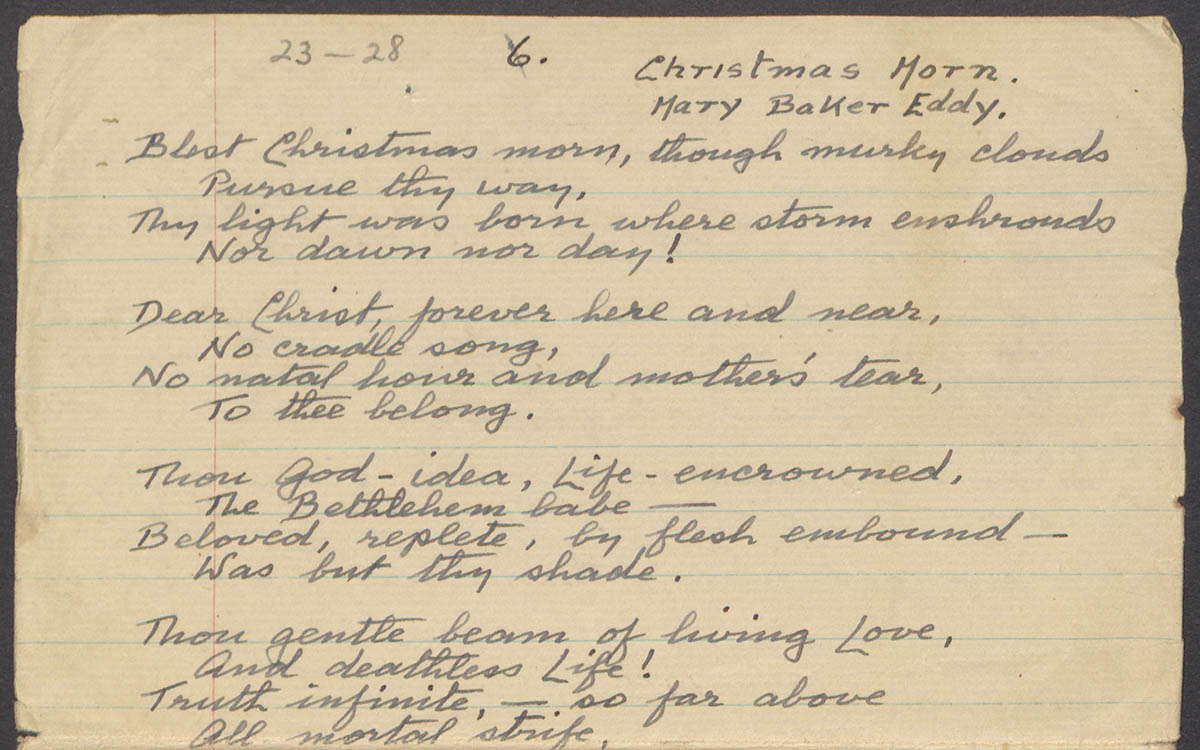

Copied hymn: “Christmas Morn,” with words by Mary Baker Eddy. “Hymns used by 1st Church Hong Kong, China at Stanley Internment Camp (1941–1945),” Church Archives, Box 38860, Folder 172670.

On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked the Pearl Harbor United States military base near Honolulu, Hawaii. The next day it launched an assault on Hong Kong, 5,500 miles to the southwest. Just two weeks later, on Christmas Day, Hong Kong surrendered, leaving approximately 3,000 non-Chinese, non-Axis civilians in Japanese hands.

While soldiers were sent to camps for prisoners of war, different arrangements had to be made for the captured civilians. In January 1942 Japan established Stanley Internment Camp on a peninsula housing a fort, a college, a preparatory school, a village, and a prison.1 The camp’s occupants came from a variety of national and religious backgrounds. Most were British, but there were also several hundred Americans, as well as Canadians, Dutch, and others.2 Among the religious groups in the camp were Catholics, a variety of Protestant denominations, and Christian Scientists.3 The Mary Baker Eddy Library’s archives hold records and mementos of the services that Christian Scientists established during their time of imprisonment. These records reveal a remarkable story of persistence and resilience that still inspires 80 years later.

While the Stanley was neither a prisoner-of-war camp nor a concentration camp, conditions were certainly harsh. When civilians were first ordered to assemble, they were not told they were being interned. Unable to return home, they were only allowed to bring into the camp what they carried with them. Conditions were cramped. Bungalows built to accommodate four people at St. Stephen’s College now housed 30 or more. Most internees were held on the grounds of Stanley Prison, though not in the prison structure itself. The greatest challenge most of them faced was getting enough food. They received two meals a day, generally a small bowl of rice and some watery stew. Illness and digestive issues were common. Circumstances would have been even more difficult, but for the relief supplies sent by friends and the Red Cross, and what could be purchased through the camp canteen and on the black market.4

Annette Rowell was one interned Christian Scientist. She recounted this in a testimony published in the Christian Science Sentinel on October 19, 1946:

I arrived in Stanley Internment Camp with only such things as could be carried in two small baskets, the most precious of all being my Bible and Christian Science textbook. The demonstration of supply was almost like that of the loaves and fishes. Never did I forget to thank God many times a day, knowing that He is the only source of supply and can and does meet my every human need. Surrounded by nearly three thousand people burdened with the fear of starvation, I can gratefully say I never once felt the pangs of hunger. I was wonderfully sustained, and received strength day by day.5

Indeed, religion was a great comfort to many in the face of their numerous challenges and hardships. The Japanese were largely tolerant of religion there and allowed faith groups to hold church services. While many groups joined together to worship collectively, Christian Scientists held their own services, as did others.6

Records of these Christian Science services reveal the trials faced in the camp, as well as the resilience and sense of community shown by the participants. A quarterly report by the clerk, dated February 23, 1945, discussed some of the difficulties they encountered. One issue was the physical conditions. Although it was reported that services were largely carrying on well, the Social Hall where the meetings took place had become increasingly cold. While organizers considered relocating, they made the decision not to do this, because they might not have been able to sing hymns.7. Another issue that arose involved the risk of air raids during church. On April 25 the group decided that, in the event of an air raid, services would carry on as usual. However, the hymns would be read by the Reader, rather than sung by the congregation.8

Another significant challenge was the lack of access to Christian Science literature. Unlike denominations with ordained clergy, Christian Scientists required access to the Bible and Mary Baker Eddy’s writings, including the weekly Lesson-Sermons created by The Mother Church and published in the Christian Science Quarterly. The Sentinel dated February 2, 1946, included this report:

Notwithstanding the fact that everything taken into the camp had to be carried on the backs of the internees, the Christian Scientists were able to provide sufficient literature to meet the needs of the small early congregations. As the number of those interested grew, along with the desire to study Mrs. Eddy’s works, the need was met by the arrival of two unexpected parcels of books and periodicals. These had been purchased at street bookstalls by the few members, Chinese and Third Nationals remaining in Hong Kong, who made this their loving task until the Japanese Administration refused to allow the sending in of printed matter to the camp.9

The lack of access to current issues of the Quarterly was particularly challenging. Readers needed the citations to passages from the Bible and Eddy’s book Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures in order to conduct services. A 1942–1943 report of the Literature Distribution Committee outlined how the interned Christian Scientists responded to this need:

At first, handwritten copies were made of the C.S. Quarterly (October–December 1942 and January–March 1943) which had been brought in, but as the number of students grew this was found to be difficult, and now thro the kindness of a member a sufficient number of copies is being typed out to meet the weekly requirements ….10

On March 9, 1945, meeting minutes of the branch’s Board of Directors expressed gratitude for issues of the Quarterly received in parcels from the United States.11 The Committee on Publication for Canton and Hong Kong later reported that this was the first time in years that they had been able to “keep in step with the rest of the world.”12

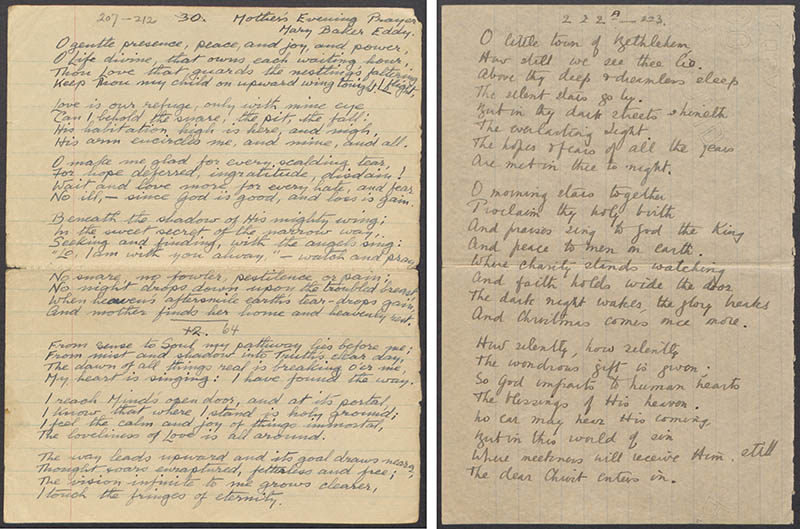

Copied hymns: “Mother’s Evening Prayer,” with words by Mary Baker Eddy and “O Little Town of Bethlehem,” with words by Phillips Brooks. “Hymns used by 1st Church Hong Kong, China at Stanley Internment Camp (1941–1945),” Church Archives, Box 38860, Folder 172670. View a larger image

In addition to issues of the Quarterly, the interned congregants had difficulty obtaining the words to hymns from the Christian Science Hymnal, which are integral to church services. Evidently these were transcribed by hand so that more individuals could participate. The Library’s archives contain multiple copies of these copied hymns, including those with words to Eddy’s poems “Love,” “Mother’s Evening Prayer,” and “Christmas Morn,” as well as Phillips Brooks’s “O Little Town of Bethlehem.” Hymns such as these may have been sung at the Thanksgiving services, which the interned Christian Scientists held on New Year’s Day.13 A report of the clerk described one such service:

This was a specially impressive service held in room 34 A.3 on New Year’s afternoon. A record attendance of 24 was present all earnestly wishing to give thanks to God for his loving care and goodness.14

On August 18, 1945, news came through the Chinese press that the Emperor of Japan had accepted the terms of surrender to the Allied forces.15 The following year, Annette Rowell published her testimony in the Sentinel. During the time she was interned at Stanley, she had served as a First Reader in the Christian Science worship services. While everyone’s story is unique, this description of how faith sustained her during those difficult years might mirror the experiences of interns from her own, and other, denominations:

The abnormal conditions under which I lived in the camp forced the errors of impatience, intolerance, resentment, self-pity, and self-condemnation to the surface, and they had to be handled again and again. Through constant prayer, watching, and consecrated effort I have been enabled to impersonalize them and see their nothingness, proving what our beloved Leader, Mary Baker Eddy, says on page 118 of “Miscellaneous Writings”: “The warfare with one’s self is grand; it gives one plenty of employment, and the divine Principle worketh with you, —and obedience crowns persistent effort with everlasting victory.”16

To hear more about the power of hymns, including those in the Christian Science Hymnal, listen to “Hymns for our time—a conversation with Ruth Duck”, a Seekers and Scholars podcast episode.

This article is also available on our French, German, Portuguese, and Spanish websites.

- Geoffrey Charles Emerson, “Stanley Internment Camp, Hong Kong, 1942–1945: A Study of Civilian Internment during the Second World War,” MA Thesis, (University of Hong Kong, 1973), 1, 3, 8.

- Emerson, “Stanley Internment Camp,” i.

- Emerson, “Stanley Internment Camp,” 201.

- Emerson, “Stanley Internment Camp,” 6, 11, 16, 84–85, 88–89.

- Annette M. Rowell, testimony, Christian Science Sentinel, 19 October 1946, 1836–1837.

- Emerson, “Stanley Internment Camp,” 202, 204.

- “Quarterly Report,” 23 February 1945, Church Archives, Box 38860, Folder 172031.

- “Meeting Minutes,” 25 April 1945, Church Archives, Box 38860, Folder 172183.

- “Christian Science Committee on Publication for Canton and Hong Kong, China, Reports,” Christian Science Sentinel, 2 February 1946, 203. See pages 203–204 for the entire report.

- P. A. Ayrton, “Literature Distribution,” 1943, Church Archives, Box 38860, Folder 172563.

- “Meeting Minutes,” 9 March 1945, Church Archives, Box 38860, Folder 172183.

- “Christian Science Committee on Publication for Canton and Hong Kong, China, Reports,” Sentinel, 2 February 1946, 203–204.

- In the Manual of The Mother Church, Mary Baker Eddy provided for an annual Thanksgiving Day service with its own Lesson-Sermon. In the United States, Christian Scientists hold this service on the fourth Thursday of November. In other countries with a Thanksgiving holiday, it is generally held on the appropriate date. In countries without a Thanksgiving holiday, congregations may choose a day on which to hold the annual service.

- “Clerk’s Report: Annual Meeting Year ending Nov. 1944,” c. 1944, Church Archives, Box 38860, Folder 172447.

- Louie Stops, “Raising the Union Jack at Hong Kong,” The Christian Science Monitor, 19 October 1945, 18.

- Annette M. Rowell, testimony, Christian Science Sentinel, 19 October 1946, 1836–1837.