The “record of dreams”: documenting George Glover’s guardians

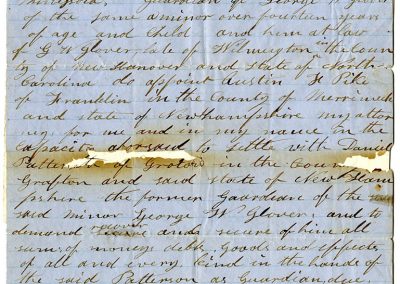

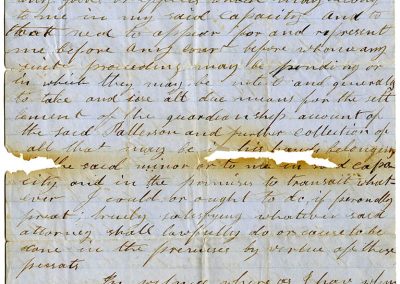

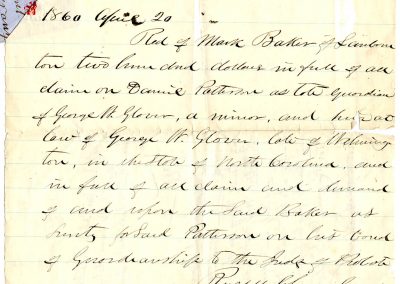

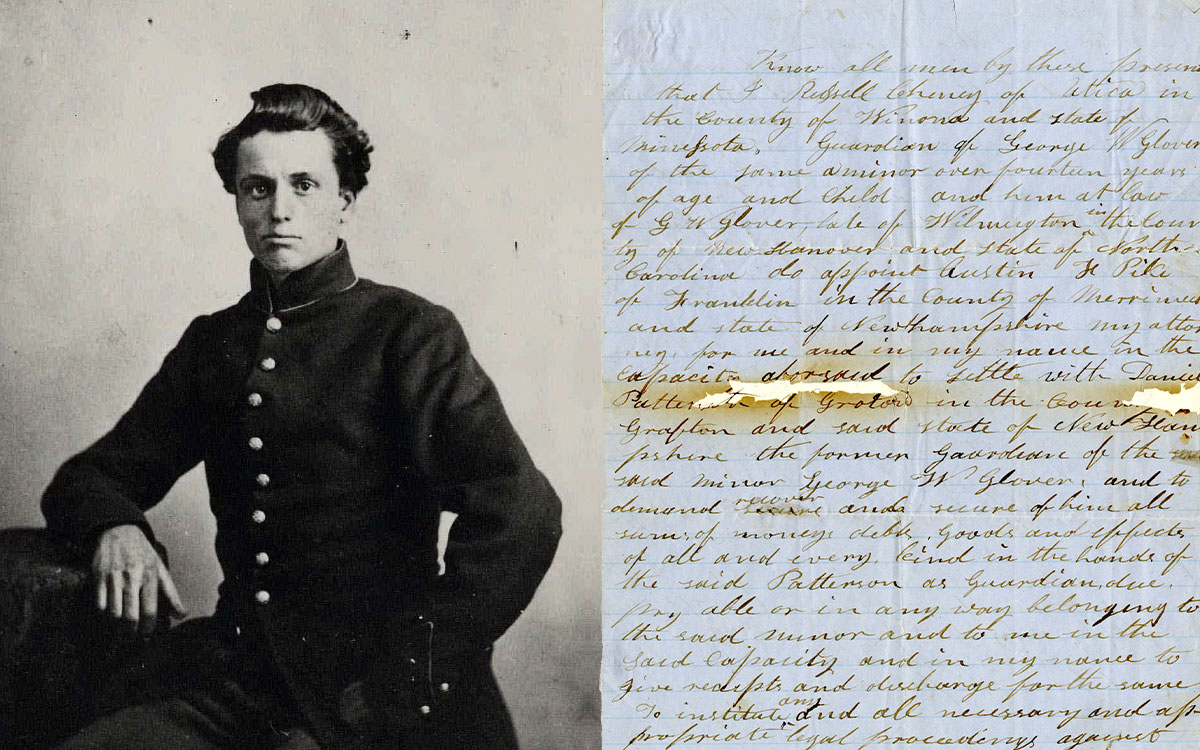

Studio portrait of George W. Glover II, posing in military uniform, c. early 1860s. P00801. J. H. Phillips. Document detailing Russell Cheney’s guardianship of George W. Glover, September 25, 1859. Subject File – Glover, George Washington II – Guardianship Papers (Cheney Family).

We have in our collection two fragile papers, found in the safe deposit box of Mary Baker Eddy’s grandson George Washington Glover III. They furnish a key piece of information about the early life of his father, George Washington Glover II, who was Eddy’s only child.

Some background information helps to set the scene. George Washington Glover II was born on September 12, 1844, when Eddy (then Mary M. Glover) was 23. Her husband, George Washington “Wash” Glover, had died about three months earlier, after only six months of marriage. As a woman she could not be her son’s guardian; young George was the legal responsibility of Mark Baker, his maternal grandfather. The boy also became Baker’s financial responsibility. Employment opportunities for women were limited and paid poorly in rural New Hampshire, where Eddy and George lived with her parents until late 1850. By then Mark Baker was remarrying—his wife Abigail had died the year before—and he decided that his daughter and grandson should move out.

Eddy’s only real choice was to live with her sister, Abigail Baker Tilton. But the rambunctious George was not welcome there. Mark Baker had a solution: George would live with Mahala Cheney, a trusted former family servant who lived with her husband, Russell, on a farm in northern New Hampshire. Eddy’s anguish over this turn of events is vividly expressed in a poem she wrote at the time: “Oh, life is dead, bereft of all, with thee,— / Star of my earthly hope, babe of my soul.”1

Eddy could never be George’s legal guardian. But if she remarried, her husband could, through court appointment, take on that responsibility. As she later recalled, “My dominant thought in marrying again was to get back my child, but after our marriage his stepfather [Daniel Patterson] was not willing he should have a home with me.”2

These papers from a safe deposit box document an unforeseen, and unwelcome, development: Russell Cheney’s aggressive and successful attempt to obtain money from George’s family. Cheney had been appointed Glover’s guardian earlier in 1859, and he targeted Eddy’s second husband, Daniel Patterson, whom he incorrectly identified as the boy’s former guardian. In fact, the Pattersons had no money to spare. They were bankrupt and dealing with the foreclosure of their home in North Groton, New Hampshire.

Mark Baker responded to Cheney, paying him $200 (about $7,400 in today’s money).3 The documents do not mention George’s mother, and it seems likely Eddy knew nothing about her father’s payoff of Russell Cheney. This was perhaps one of the most harrowing periods of Eddy’s life. She said this after recounting the story of her son’s removal in her autobiography:

It is well to know, dear reader, that our material, mortal history is but the record of dreams, not of man’s real existence, and the dream has no place in the Science of being. It is “as a tale that is told,” and “as the shadow when it declineth.” The heavenly intent of earth’s shadows is to chasten the affections, to rebuke human consciousness and turn it gladly from a material, false sense of life and happiness, to spiritual joy and true estimate of being.

The awakening from a false sense of life, substance, and mind in matter, is as yet imperfect; but for those lucid and enduring lessons of Love which tend to this result, I bless God.4

About six years later, Eddy’s life would begin to change, with such an “awakening”—her discovery of Christian Science.

This article is also available on our French, German, Portuguese, and Spanish websites.

- Mary Baker Eddy, Retrospection and Introspection (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 20.

- Eddy, Retrospection and Introspection, 20.

- See Gillian Gill, Mary Baker Eddy (Reading, Massachusetts: Perseus Books, 1998), 114–115. For more information on these documents and their importance in understanding Eddy’s relationship with her son, see Jewel Spangler Smaus, “An important historical discovery,” The Christian Science Journal, May 1983.

- Eddy, Retrospection and Introspection, 21.