What were some ways The Mother Church responded to racial unrest in the 1960s?

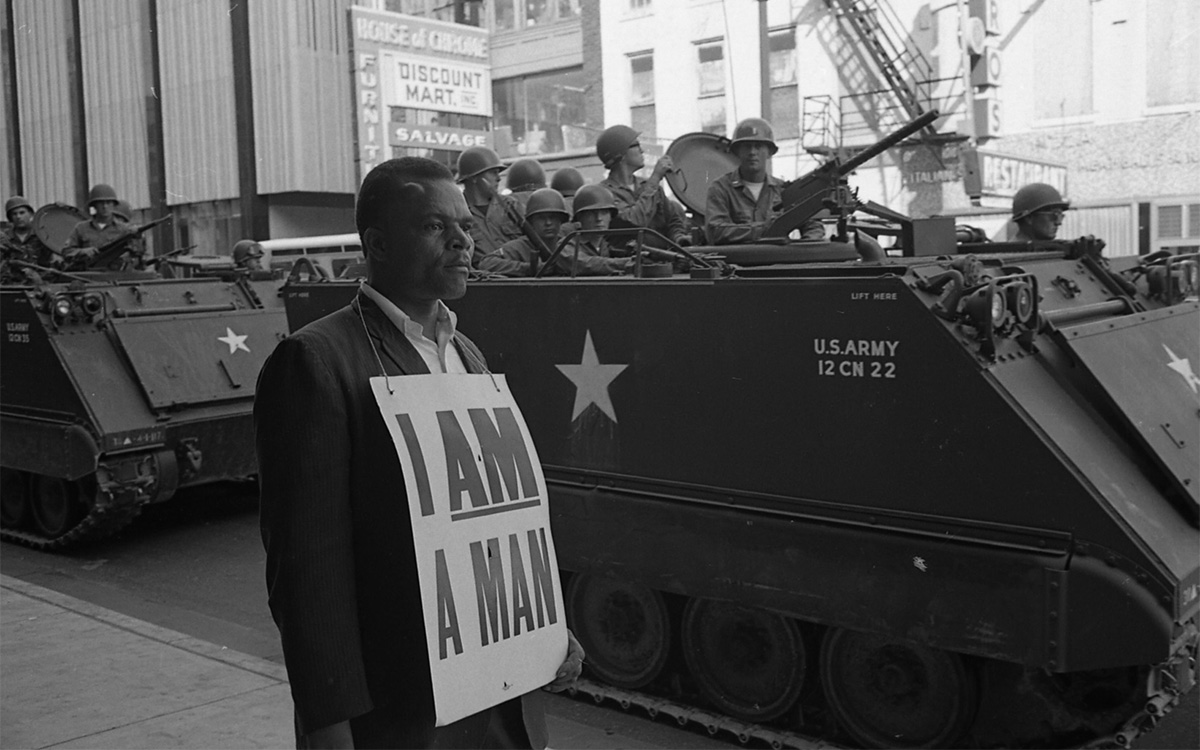

This staff photo by Norman Matheny appeared in The Christian Science Monitor on April 1, 1968, with this caption: “Picket and patrol: Both protestors and National Guardsmen took up posts in Memphis streets after riot.” © The Christian Science Monitor.

Demonstrations following the deaths of George Floyd and other Black Americans are being compared with the unrest that shook the United States in the 1960s. Though the two time frames and their protest movements are not, of course, identical, we wondered how The Mother Church (The First Church of Christ, Scientist) responded to the racial protests that attended the ferment in the 1960s. With its headquarters in what was often referred to at the time as Boston’s “inner city,” The Mother Church was at a crossroads of activism, conflict, and demands for equality.

Then and now, The Christian Science Monitor—through its reporting, editorials, and opinion pieces—provided the most visible evidence of the church’s engagement with racism and injustice, and their solutions. The Monitor’s Howard James won the 1968 Pulitzer Prize for reporting on national affairs; his “Crisis in the Courts” delved into issues of justice and equality that are still relevant.1 In fact, as a June 2020 opinion column writer in Maine’s Bangor Daily News pointed out, some of the Monitor’s coverage of racism in the early 1960s sounds all too familiar today:

“My father, Robert C. Nelson, a correspondent for the Christian Science Monitor, covered the integration of Ole Miss. His original coverage provides me perspective in the age of George Floyd and the global protests in reaction to his death…. Dad witnessed and wrote about it all…. His lede, written on Sept. 30, 1962, seems current: ‘All the ugliness of a mob unleashed swirled around the decisive, historic final effort to register a Negro [sic] at the University of Mississippi.’”2

To understand Black Americans’ interaction with The Mother Church during the racial unrest of the 1960s, it is important to look further back at the history of Christian Science.

In 1879 Mary Baker Eddy and a small group of her students voted “to organize a church designed to commemorate the word and works of our Master, which should reinstate primitive Christianity and its lost element of healing.”3 Recently, the Mary Baker Eddy Papers published the earliest known correspondence with Eddy about healing among Black Americans, dated 1881. Some Black people became early adherents and members of The Mother Church in the 1890s and 1900s. For example Leonard Perry, Jr., of Washington, D.C., joined the church in November 1900 and was first listed in The Christian Science Journal as a practitioner in 1906. He served the movement until his passing in 1949. A testimony by another Black Christian Scientist, Marietta Webb, is included in “Fruitage,” the final chapter of Eddy’s book Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures.4 In an 1899 article in the Christian Science Sentinel, Webb wrote this:

…I verily believe [Christian Science] is to be the only salvation of my race, the Afro-American, and that it will abolish the prejudice which exists throughout these United States; for, go where we will, we are made to feel our color.

But with the wide and rapid spread of Christian Science man is not only learning what the true love of God is, by loving all mankind; but he is getting out of his old prejudiced self, into the spiritual sense of man’s union with God.5

Black Christian Scientists were increasingly made to “feel their color” in the early twentieth century. Black people attending church alongside whites, and access to membership and leadership positions, became matters of contention in some areas. Christian Science branch churches are lay organizations without ordained clergy; racist enactments varied from place to place. These arguments were not confined to the South. They were also pronounced in the Midwest and, later, in California.

In 1919 the Christian Science Board of Directors formed the Committee on General Welfare, to investigate a number of issues.6 Its wide-ranging 1920 report included this:

Q. Should there be segregation of the colored race in Christian Science churches?

A. The Committee believes that the race question is slowly being solved on the basis of Christian Science and that mankind is in the melting pot in which all races are being refined and regenerated, until their false personality expressed in color and national prejudice shall pass away. The question being an extremely complex one, it must necessarily be approached with courage, hope and love. At present no doubt, some degree of consideration should be given to custom, condition and environment. What may be desirable in one community may be wholly undesirable in another, so that the segregation or mixing of the colored people in Christian Science churches must be a question for local determination. When both the white man and his darker skinned brother understand enough of Christian Science their natural differences will disappear. In working out this demonstration all need to be charitable, unselfish, forbearing, and kind. In localities where colored people are not accustomed to mingling with the whites, they cannot consistently expect an immediate change from such a long custom, but it would seem that patience and the demonstration of the higher and better qualities of character are more essential than the correction of social inequalities.7

Advocacy for “local determination” recognized the democratic self-government of branch churches. But in 1922, just a few years after this report, it was The Mother Church—through the directory of the Journal—that began using the qualifier colored to designate the names of Black Christian Science practitioners and Christian Science nurses, as well as branch churches that were predominantly Black. This practice would prevail until 1956.

Historian Thomas Johnsen explained the “advent of institutionalized segregation”: “The Great Migration of African Americans from the South in the 1920s brought a substantial influx of new converts in Northern and Western cities, but these increasing numbers elicited increasing resistance from portions of the [Christian Science] church membership.”8

Local conditions also played a role. Johnsen provided this example:

Annie Julia Roberts…was born into slavery in Mississippi in 1862 and joined the local Christian Science congregation in Prescott, Arizona, in the early 1900s. She served as a Christian Science practitioner for more than twenty years. In a 1945 obituary, the Prescott newspaper reported that both whites and blacks sought her help for healing. The obituary noted the unusual affection between Roberts and other members of the mostly white congregation, reflecting that the spirit she expressed far surpassed the limits society imposed.9

Lulu M. Knight of Chicago became the first Christian Science teacher of African descent in 1943. By 1950 Ebony magazine had reported a situation in the church that was complicated and untenable:

In the South the church complies with existing patterns and state laws which prevent race mingling but in Washington, D.C., Negroes and whites attend the same churches. In Birmingham, Alabama, Negro and white members of the church used to meet together but they now hold separate gatherings due to intensified agitation for racial segregation by city officials. The two groups would like to meet together but the “law” forces them to observe Jim Crow….10

The 1960s began to see changes. Knight was on the program at the Annual Meeting of The Mother Church in 1961, reading reports of healing that were an important feature of that gathering.11

The religious periodicals published articles that reflected an increasing awareness of racism. Authors recorded healings and victories over discrimination in many situations, such as in the article “Spiritual Dominion,” by Cora J. Gibson12 During the 1960s and into the 1970s, a few writers told of their own experiences of racism in church and how they dealt with it—see, for example, “Healing Racism: An Interview,” in the November 1978 Journal. (For more on this subject you can also search the website JSH-Online, which includes an index to the church’s magazines from 1883 until today, using keywords such as race, racial, discrimination, prejudice, Negro, Afro-American, ghetto, inner city, and related terms.) These articles and testimonies came from all over the Christian Science field. Concurrently, Christian Science was gaining a stronger foothold in sub-Saharan Africa, further diversifying the church’s membership. The Monitor covered independence movements on that continent extensively.

The Watts Rebellion of 1965, and the “Long, hot summer” of 1967, challenged the United States, including its religious communities. But some of the deepest demands on The Mother Church to respond to racism were made locally. When civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated on April 4, 1968, unrest broke over the country in waves of grief, anger, and despair. The city of Boston was shaken, but somewhat peaceful in the immediate aftermath.13 Like many houses of worship, The Mother Church held a memorial service in its Extension on April 9, in commemoration “of the life and contribution of the Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King, Jr., Nobel Prize winner and leader in this nation’s movement toward peace and the equal rights of all men” (the service begins at 13:40 in the link above). The opening hymn of the service included these words:

Come, ye disconsolate, where’er ye languish,

Here health and peace are found, Life, Truth, and Love;

Here bring your wounded hearts, here tell your anguish;

Earth has no sorrow but Love can remove.14

During the June 2, 1969, Annual Meeting, the 15-member “Metropolitan Boston Committee of Black Churchmen” insisted on reading a list of demands, including money, a financial accounting of the church, the conferral of church property in a Black neighborhood to the Black community, and an upgrading of Black employees’ status, among other things.15 “Polite applause” followed the Committee’s statement. But the Monitor published a response from the Board of Directors a few days later, in which they declined to meet any of the group’s demands.16

At a June 4 meeting for members two days later, the theme “Facing the Great Challenges” focused on “three areas: law, order, and justice; understanding youth; and brotherhood and racial harmony.”17 (The section on “brotherhood and racial harmony” start at 52:20.) In framing these issues, the meeting’s chair remarked that “each of these three challenges is what political leaders have called ‘a crisis of the spirit.’’’ Monitor reporters interviewed thought leaders in the focus areas. Talks by Christian Scientists followed. The film of this event was distributed for local viewing to branch churches. In his talk, Alton A. Davis, a Black member, said: “This is the problem today: not the world, but how we judge one another.” He asked:

When you…realized you had a black neighbor, was your world shattered? When your little girl came home from school and told you that a black boy and a black girl had been enrolled in her school, was your world shattered? If such experiences shatter your world, then your world is but your own narrow concept of your fellow man…. If we are honest, we must admit that it is the passivity of Christians that must be blamed for the continuance of world unrest. Christian passivity is the crime of the century. Brotherhood is not the absence of hate, it is the active presence of love. The posture of Christian Science, as it comes to grips with this great evil, racial inharmony, is vividly illustrated in the story of David and Goliath. Numerically, perhaps Christian Science is one of the smallest of the great religions of the world; yet Christian Science, like David, comes forth to do battle with a formidable giant, arrayed in hypocrisy, hate, racial prejudice, bigotry, “spiritual wickedness in high places.” And like David, Christian Scientists can gather the spiritual stones with which to slay this giant. These stones are the qualities of Christ, Truth: patience, humility, kindness, understanding, brotherly love. Mrs. Eddy says, “No power can withstand divine Love.” Christian Scientists must be governed by spiritual consciousness and bear the criticisms of the world. They must “come out and be separate.”

The building of the Christian Science Center began in 1966.18 The Mother Church expanded the footprint for its headquarters by demolishing its own administrative building, adjacent commercial space on Massachusetts and Huntington Avenues, and over 500 units of housing. Controversy over the displacement of residents, some of them Black Americans, and of their relocation was closely covered in the city’s press. The church provided financial and relocation assistance, but the most concrete indication of its commitment to rehousing Bostonians was the construction of the privately owned Church Park Apartments across Massachusetts Avenue from the church—at that time the largest apartment building in the city, with units reserved for low-income renters.

The construction of the Christian Science Center employed thousands of workers. The church developed an apprenticeship program with some of the contractors, to train minority youth in the skilled trades.19

In August 1969 Christian Scientist students and faculty gathered in Boston for a biennial college meeting, with the theme “Building in a Revolutionary Period.”20 Students had taken an enlarged role in planning and leading the sessions, which stretched over several days. Questions about conscientious objection to military service, about use of “the pill” for birth control and its compatibility with the teachings of their religion, and about racial equality, were discussed in student-led sessions and in a meeting with the Directors. One attendee remembered that the Directors agreed that race issues related to continuing segregation in branch churches, especially in the southern US, needed attention.

The Directors published “Healing Racial Divisions” in the July 1971 Journal, a statement reminding readers of the need for “more than vague goodwill” in addressing the climate of racism. It concluded:

In today’s racial crisis there is no use saying: “This is not my problem. I am not a racist. I mind my own business. I’m kind to people of other races. Isn’t that enough?” The answer, for the Christian Scientist, is No! Nothing short of healing the problem is enough. Healing it requires prayer acknowledging the universality of God’s love; and individual attitudes in accord with this love.21

The Mother Church’s response to the racial unrest of the 1960s showed how far the church had come—and how far it still had to go. The earlier designation of practitioners, nurses, and branch churches as colored had officially marginalized them for over 30 years. And attitudes toward race that implied “colorblindness” tended to render Black Americans invisible, by failing to acknowledge how their experience differed from that of whites. By contrast Marietta Webb, Alton Davis, and others sought to elevate race relations, combining recognition of spiritual truths with calls for individual and collective redemption. These calls challenged Christian Scientists—and still challenge them—to practice what they preach, for “the healing of the nations.”22

Click here to read this article in The Christian Science Journal, along with coverage of a June 2020 Mother Church meeting for local members that addressed protests for racial justice and equality in the city of Boston.

- https://www.pulitzer.org/winners/howard-james, accessed 6/24/2020.

- Todd R. Nelson, “My dad’s 1962 reporting echoes through today’s protests,” 5 June 2020, https://bangordailynews.com/2020/06/05/opinion/contributors/my-dads-1962-reporting-echoes-through-todays-protests/, accessed 24 June 2020.

- Mary Baker Eddy, Manual of The Mother Church, 17.

- Mary Baker Eddy, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, “A Remarkable Case,” 612–614.

- Marietta Webb, “The Protecting Power of Truth,” Christian Science Sentinel, 23 November 1899, https://sentinel.christianscience.com/shared/view/2kv1sm325u6?s=t, accessed 24 June 2020.

- “Annual Meeting of The Mother Church,” Sentinel, 14 June 1919.

- “Report to the members of The Mother Church of the Committee on General Welfare” (New York: Federal Printing Company, 1920), 19–20.

- Thomas Johnsen, “Christian Science,” American Religious History: Belief and Society Through Time, Ed. Gary Scott Smith (Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2020).

- ibid.

- “Christian Science,” Ebony, November 1950, 60.

- “Annual Meeting of The Mother Church,” The Christian Science Journal, July 1961, 353, https://journal.christianscience.com/shared/view/kz0tvblseg?s=t.

- Cora J. Gibson, “Spiritual Dominion,” Sentinel, 8 April 1972.

- Alan Lupo, “Tension, but Self-Control,” The Boston Globe, 6 April 1968, 1.

- Christian Science Hymnal, No. 40.

- “Black Demands in Boston,” Newsweek, 16 June 1969, 88.

- “Church replies to demands,” Monitor, 9 June 1969, 5.

- Office of Records Management, the Mary Baker Eddy Library, Media Archive product description. n.d.

- “Church Center Progress,” Sentinel, 17 December 1966, 2224–2225

- “Minority Employment and Training: Church Center Construction Project,” 16 November 1970, Church Archives, box 37963, folder 161080.

- “The 1969 Biennial College Meeting,” Sentinel, 15 November 1969, 2018–2019.

- The Christian Science Board of Directors, “Healing Racial Divisions,” Journal, 10 July 1971.

- Rev. 22:2.